Tags

Bowfin Country, Hank veggian Fishing, Jackson Coosa, Kayak Bass Fishing, kayak fishing, kayak fishing north carolina, Kayak Fishing Posts, learning the water, Shearon Harris

The Question

How do we learn to fish? And more specifically, how do we learn to fish a specific body of water? The two questions address two interdependent types of education. The former is a general skill set, such as one obtains with a liberal arts degree. The latter is specialized, like a Master of Business Administration or Master of Fine Arts degree. In short, we take the general skill set and apply it to a specific body of water. We refine and fine tune, match the universal with the local, and ultimately pair the species with the phylum. By adapting our general skills to the specific lake or pond or river, the adaptation may also change our general skill set. Ideally, by way of the back and forth, we may become versatile.

The give and take between general skills and a river or lake can resemble a positive teacher-student relationship. At other times, it makes you want to send the whole class to detention.

There is also the risk that a specific fishery will spoil us. An angler may become the star pupil who is never challenged by a teacher or classmate. The angler adapts to it, but then takes those lessons and applies them everywhere else, regardless of conditions. It’s like a college coach who travels from school to school, selling his or her “program” to the highest bidder. Sure, it may work at some schools, but the original, specific set of circumstances – a place and time – can never be repeated. We can only hope for an approximation.

A final note: as we refine fishing techniques on one lake or river, we learn to adapt techniques not just there, but anywhere. That is to say that as we learn how to fish, we also learn how to learn.

I have been writing up my history of kayak fishing on specific lakes in the Triangle region of North Carolina. My focus has been on bass fishing. In a previous article, I examined my history on Falls Lake. In this article, I review my experience on Shearon Harris reservoir, the second of the region’s “big three” bass fisheries. I will review Jordan Lake, the third one after Falls and Shearon Harris, later this summer (I have been writing the articles shortly after recent kayak fishing tournaments on the lakes).

Each article is a case study, if you will. Of course, the times and places cannot be repeated. But we can discern patterns in seasons and water levels, strategies and techniques, or areas of the lake; again, I caution that general principles have to be refined to the occasion, but that is the art of fishing, isn’t it? Smart anglers accumulate experience, reflect upon it and adapt. Again, we learn how to learn.

Or do we? Sometimes, we trick ourselves into thinking we do. Harris is that sort of lake: it can make a fool of you, no matter how educated or experienced you are. And it can also make a fool appear to be a genius. After many years, I have come to earn advanced degrees in both subjects.

Shearon Harris

We call it “Harris.” When an angler announces “I am going to fish Harris,” there is promise and menace in the declaration. He or she may find El Dorado or they may come home empty-handed. We all know about the famous limits a boater caught there in 2017 that weighed over forty pounds, and the lake’s legendary big bites.

One evening in 2016 or 2017, I watched a boater lose the bass of a lifetime along the old grass on the lake’s east end. I saw the cast and watched the big swirl as the bass inhaled a hollow-bodied frog. It was a harrowing fight – the bass kept running under and around the boat. Finally, the bass wrapped the line on the shaft of the angler’s trolling motor and got away. The poor guy fell to the deck like he’d been shot. When he didn’t resurface after about a minute, I paddled over, worried about his health. He replied with a long groan when I asked if he was okay. He was nearly in tears when he said “I’ve been waiting for that bass for thirty years.”

I saw the fish breach after it was hooked. Did it weigh twelve or thirteen pounds? It looked that big from a distance. But if that’s how it looked from a distance, it was probably bigger.

Much the same can be said for Harris. It sounds big, and may appear large in a map. It is however a small lake that “fishes big,” as some say.

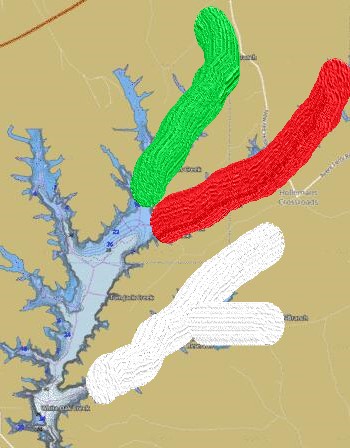

It can be divided in four sections. The first is the long arm that runs east to west (in red on the map below), on which the Hollemans boat ramp is located. This arm has a shallow, east end (above the bridge) and concludes on the main lake. Moving counter-clockwise, there is the White Oak branch (green on the map), which runs at an angle from the southeast to the north and east. This section has the reactor facility on its western shore, and has a grassy creek at the shallow, northern end.

The third section is the main lake (in blue). The two previous sections converge to form it, making an excellent deep point. The main lake is characterized by a rocky and deep eastern shore and a shallow western shore that contains several large coves. Here, the lake is at its widest, and the deeper water has many long, sloping points. This section reaches all the way to the south end of the lake, which is sealed by a dam.

The final section is what I call the great unknown (in white). It is a long arm that runs from the south and west to the north and east, ending in a large, pad filled cove. The great unknown begins across from the Crosspoint boat ramp and forks to the right. On the eastern shore, littered with laydowns, is tornado alley. The arm is narrow and long, with small indents that might be called coves, until it ends with two larger coves. There is a small creek at the farthest cove, which I accessed once and paddled down to the main lake.

I call this the last section the great unknown because few kayak anglers venture that way, and I have done so only once. The majority launch from the Hollemans ramp or the bridge, or launch at Crosspoint and turn left to the main lake. I predict that in coming years the great unknown will become more popular as motorized kayaks are more common.

That is Harris – four sections, three of them known to kayak anglers, one a mystery.

It has also four access points: two big public ramps, a small launch at the county park, and a primitive launch above the Holleman Road bridge.

A small lake, at under 4,000 surface acres of water, its reputation far exceeds its scale. I’ve met boaters on the lake over the years who have traveled from Wisconsin and Pennsylvania to fish it. After those 40 pound bags were landed in 2017, you couldn’t get near the lots for weeks.

My own experience on the lake has not matched the legend. I first fished the lake from the banks of the county park in 2007, and then later in 2009 from a bass boat. My first Harris tournament was in the spring of 2013. I landed one bass. In my next event there, the first ever CKA regular season tournament, it was cold and miserable. I did not catch a fish. In 2015, I caught two small fish. In 2016, I landed my first 20” bass from the lake, and also my first three-fish limit; that day, the top eight or nine anglers averaged over 20” per fish. I was not even close to the top ten. In my first four tournaments, I landed a total of six bass.

I fished the lake in several more tournaments over the years, primarily with CKA, and always came up short. In fact, I zeroed in events I fished there in both 2017 and 2018 (the single exception: a small, local club event in 2016, where I finished second after catching two fish).

And then in 2020 and 2021, after years of disappointment in competition, I finally cashed some checks at Harris. I placed third in the first ever live CCKF tournament, which was held on Shearon Harris in November of 2020. And then in February of 2021, I won a CKA tournament there on a brutal February day. It was an outlier – I was just fortunate to landed the biggest fish of the day, and I was lucky that another angler who landed two fish had one denied for a rules infraction.

Since that time, I have returned to form in competition at Harris, posting lots of poor results. Most recently, I failed to land a limit in a CKA event in March of 2023 and failed to land a single fish in a CKKF event in May of 2023.

I might say that I have yet to find El Dorado at Shearon Harris, but that is not entirely true. In fact, some of my best days of kayak fishing have happened on that lake. It is just that they have not happened during in-person tournament competition. The where and why is what matters here……

One evening in the spring of 2017, I was fishing with Joey Sullivan above the bridge on the east end of the lake when we came across a big school of bass. We were landing fish on every single cast until the light ran out. If the day had given us another hour of light, we would have caught several hundred fish. The school never seemed to end.

During the same season of that same year, while fishing a deep point at mid-lake, Drew Blair and I each landed well over 100” with our best five fish over the course of several days. Drew repeatedly landed limits that weighed over 25 pounds on a near-daily basis. I sent Adam Petrone to fish the spot one day in 2018 (Adam began tournament fishing with CKA in North Carolina), and he landed over 100” in a matter of a few hours. In 2019, that same area produced my personal best from Harris, a 23” Largemouth Bass. Over the course of three years, a very small area of the lake produced giant limits on a consistent basis.

What’s the difference? Note the years. In 2017, there were still large mats of vegetation in the shallow bays. That changed in the autumn, when Hurricane Matthew ripped them up and moved them out. Later still, the lake was sprayed to kill any remaining invasive vegetation and to make room for a long-term native vegetation growth project that began in 2019 (that project, for which I was an early representative of the kayak community, is still underway).

In short, between 2017 and 2019, the lake was changed dramatically by the combined antics of humans and hurricanes. The bass adapted, moving off-shore, where they now mostly reside.

The Problem

My tournament success on Harris in 2020 and 2021 gave me false hope. You can imagine why: from the first Carolina Yakfish event in early 2013, through five subsequent CKA tournaments between 2014-2018, I skunked in four events, landed one fish in two events and landed a limit in one event (2016). And those were all three fish limits. Had they been five, I would have not had a single limit.

In 2020-2021, I believed that I had figured out the lake’s intermediate bite. In my mind, that intermediate bite solved the challenge of having to scout the lake for off-shore fish, a risky bet when those fish tend to unpredictably move around. I placed in the money in two events by fishing in water that was 3’-8’ in depth. However, if you look closely, one of those events was just a lucky win. I had not figured out much at all.

Since 2020, I have fished Harris in five tournaments, all of them with five fish limits. In chronological order, they were:

CCKF: 3rd Place (November 2020)

CKA: 1st Place (February 2021)

CCKF: landed one bass (July 2022)

CKA: 22nd out of 76 (March 2023)

CCKF: last place (May 2023)

There is an overall pattern: after two successful events, I have returned to earth. My theory about the intermediate bite has not paid off. And when I get frustrated with the intermediate bite, I tend to look for fish in shallow water instead of venturing out deep.

And as I noted before (and will again in other posts), I also prefer to fish in or near moving water. Structurally speaking, Harris has very little current from its tributaries, and those are short and choked with vegetation. Therefore, I tend to fish with the wind – that is how I won the CKA event in 2021, by hopping and drifting a jig over flats and channels, and letting the wind do the work. It’s also how I tend to fish the deeper points.

The problem for me as an angler is the lack of consistent wind or currents makes it difficult to predict fish movement and behavior on the lake. General patterns such as the spawn or the fall feeding window are somewhat predictable, but where they happen on the lake can vary. By forcing me to fish away from current and rely on electronics and fish deep water, I’ve struggled to consistently catch fish at Harris.

The Lessons

We have established one thing: of the three Triangle-area big lakes, my tournament record on Harris is the least impressive. I do however love fishing the lake. Who can resist the allure of El Dorado?. What can we discern from the patterns?

A few things:

- Since the lake’s vegetation profile has changed, increasingly forcing bass off shore.

- Recreational boat traffic has increased on the lake in recent years, especially since the new NCWRC ramp was completed and opened in 2019, a factor that I believe keeps the fish in deeper water during the day time.

- Learning to fish deep water is a must, but it is also a risky bet, and requires time and good electronics.

- Harris has little current from tributaries and its wind currents are perhaps more valuable to learn.

There are false lessons embedded in the observations, too. For example:

- In what is arguably my best result (in 2020), I caught fish shallow, around a weak current, as they schooled in the autumn. Seasons matter, consistently, from lake to lake.

- The shallow bite is not gone; in the CCKF and CKA tournaments in the spring of 2023, I had several important bites near emergent plants. I simply didn’t put them all in the boat.

Of my five recent tournaments, the two most recent ones (in 2023) may hold the most clues. On those days, water was high and there was a passing front, and the bass had moved shallow. Many of the limits that won money (including the winning limit) were caught in or around vegetation. Looking ahead, I can say with a fair degree of certainty that the new vegetation is once again attracting fish. How long will it take to return? That is another matter.

And yet the fact remains that Harris is a difficult lake. Note that in the same CKA tournament in March of 2023, I was in 22nd place without having caught a limit. 76 anglers competed. That means that more than two thirds of the field struggled, too. It’s a common result on that lake.

In Conclusion

I attended NCWRC meetings for a project on Harris from 2019- 2022. During one of the NCWRC aquatic habitat project meetings, I heard a hydrologist call Harris a “giant farm pond.” Its water quality and forage base are similar to a farm pond, as is the lake’s geological profile. Largemouth bass grow big and fat, living long lives in the lake.

Harris is however a boater’s lake. It’s just big enough to make kayak fishing a challenge, and just small enough to make you think a kayak can cover most of it. It’s hard to break down, too: it’s unpredictable bass may sit in place for weeks only to vanish without notice or any motive we can discern.

It’s safe to say Harris the toughest of the big three bass fisheries in the North Carolina Triangle. But it’s also the type of fishery that can help you mature as an angler. It did for me. In 2017-2020, I fished off shore quite often on Harris, learning its deeper secrets. Those lessons transferred well to some other lakes, even local ones. For instance, after catching good fish deep on Harris in spring and early summer of 2017, I had one of my best single days in competition, landing 101.25” in a KBF on-line event in August. I was fishing deep, using patterns I had learned on Harris. In 2019, some of those same techniques put me in the money at the KBF-FLW Cup on Lake Ouachita.

I believe that what I am saying is that the techniques you learn on Harris may actually travel better than you can apply them on Harris itself. There is one exception – the winter blade bite – but that is for another article.

A local tournament director recently called Harris a “heartbreaker.” It’s appropriate – many of us have an intensely personal relationship with the lake. Our fishing dreams are sometimes founded on a terrible optimism: we insist on knowing what it can be, even when it never seems to rise up to that expectation. We stumble into a trap of our own making, like students who finally venture into the field blinded by the shine of discovery.

That may be the most important lesson of all: what does it say about us, then, that we keep going back to fish it?

First Published June 13, 2023. The author of this article was not assisted in any way by a machine in the composition of it.

© Henry Veggian. All Rights Reserved.